People like asking writers, “Where do you get your ideas from?”

I usually say that there are ideas for stories or poems all around us. The only difference between writers and other people is that we make sure we’ve got a pen and a notebook to hand, so that when an idea comes we don’t let it go. We write it down.

There isn’t a notebook in my pocket one hundred percent of the time. (Anyway, the secret isn’t just having the notebook. There’s a way of looking and listening with a sort of curiosity, or alertness, or care that comes into it as well.) But, actually, there won’t be many occasions when I don’t have a pen and notebook somewhere to hand.

To the surprise (quite often annoyance) of people around me, I do start scribbling things at odd moments: when walking along a busy pavement…or watching a film at the cinema…or in the middle of the night…

And If you ask around, notebooks of story ideas, observations, memories, fragments of overheard language, and other descriptions and scribbles are the foundations on which very many writers build their work.

The German author and philosopher, Walter Benjamin included the following in his thirteen pieces of advice on the writer’s technique: “…keep your notebook as strictly as the authorities keep their register of aliens.”

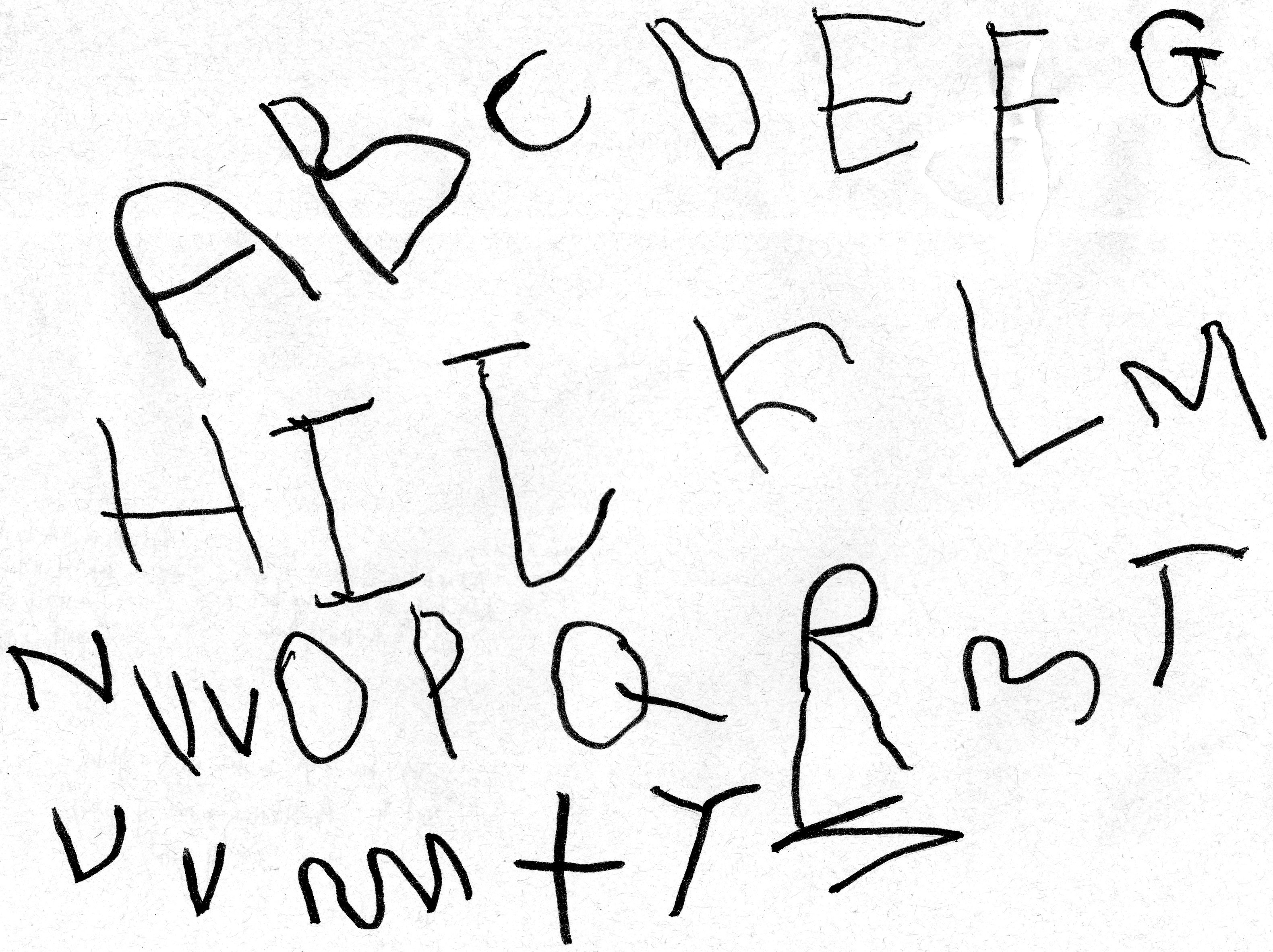

I like spiral-bound notebooks. As I go along, I destroy them! I tear out the pages. I cut them up. I throw things out. Then (sometimes by typing them on to my computer, sometimes by putting them in actual files on shelves) I sift what I’ve written into a whole lot of different categories.

So instead of having piles of old notebooks, I’ve got strange files of bits of paper.

One file has names for characters in it. Another is full of bits and pieces of dialogue. Another holds ideas for story titles.

And those are the predictable ones. If I look through, I’ve also got a file containing names of dog breeds. Another contains names of breakfast cereals. And one’s labeled COWBOY LANGUAGE,

If a hurricane ever hits my writing studio, a lot of strange confetti is going to fly!